NORTHEAST ASIAN HISTORY FOUNDATION 09/2022

-

Jeon Seong-hyeon, Professor at Dong-A University

‘Aggressors’

After the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government, trying to invade Joseon (Korea) under the pretext of revising the treaty, signed the Korea-Japan Treaty of 1876 in February 1876 by force. Shortly after that, the Busan Port Concession Treaty was signed, and Japan established Choryang Port in Busan as a settlement for the Japanese. As ports, such as Wonsan and Incheon, opened one after another, the Japanese gradually entered Joseon. Until 1905, when Joseon was reduced to Japan's ‘protectorate,’ these Japanese came to Joseon and carried out an “invasion of Korea from below,” whether it was a personal desire for quick succession or a national desire for imperialist aggression. In addition, they gradually formed a Japanese society (association of settlers, settlement corporation, etc.) centered on the open port and open market, their residences in Joseon, and actively expanded their influence. Furthermore, they played an active role as a ‘spearhead’ for Japan’s colonization of Joseon by helping the Japanese government that intended to make Joseon their colony entirely and serving as a guide in the Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War. Through this process, the number of Japanese in Busan, only 54 at the time of the port opening, exceeded 30,000 by 1905. They began to change from being the bridgehead of the Joseon invasion to the ‘grassroots colonizers’ of Joseon rule.

‘Colonizers’

The Japanese, who migrated and settled in Joseon for the invasion of Joseon after the opening of the port, formed a Japanese society centered on the open port and started to live their lives as ‘grassroots colonizers’ with the ‘imperial perspective’ as imperialists and the ‘perspective of Joseon’ and the ‘region’ as colonialists. They promoted suffrage and petition movements in Japan along with the special self-governing system to maintain their interests and privileges as colonizers while actively participating in the 'local council' of colonial Joseon to push forward with colonial policies and colonial rule for themselves through central and local politics. In addition, to maintain the identity of Japanese colonizers and their own community, they installed Shinto shrines and licensed quarters, which is Japanese culture, in local communities and expanded them to the Korean settlements to intensify colonization. In particular, Shintoism was converted into National Shintoism. It functioned as an important foundation for producing people who would serve Japanese imperialism and war. The licensed quarters were one of the factors that influenced the strong persistence of colonial patriarchy. Not only that, they were the ones that predominantly enjoyed the modern urban infrastructure and culture partially introduced into the colonies. They fully enjoyed the modern culture introduced into the colonies, such as railroads, trams, electricity, and telephones, as well as leisure, tourism, and consumption, in their community.

‘Marginal People’

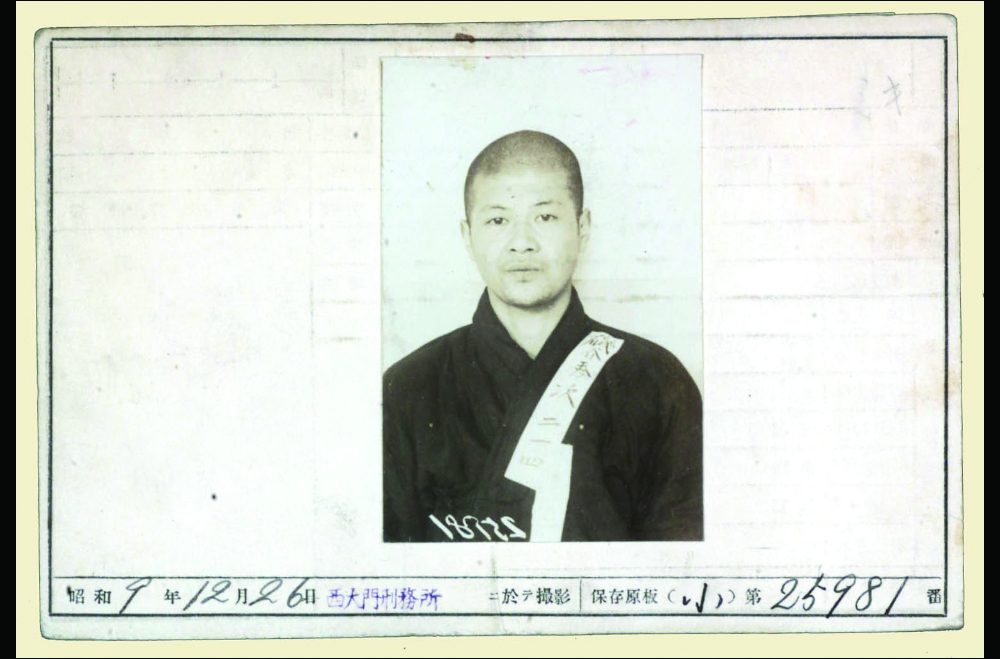

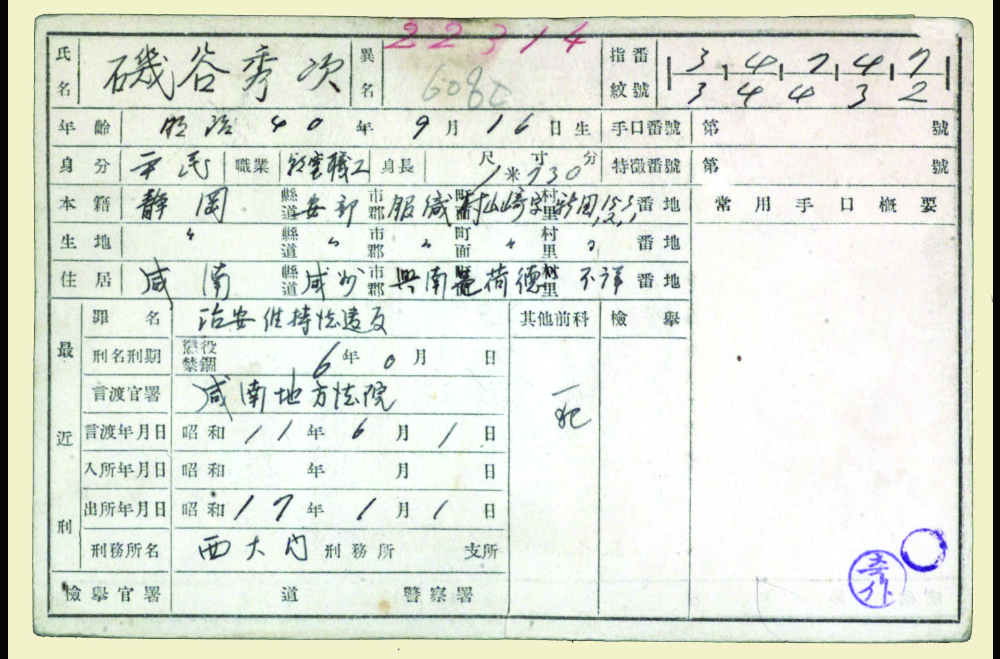

Of course, not all Japanese in colonial Joseon became established as colonizers. There were also Japanese who belonged to the lower classes in terms of class, status, and gender. However, even at the bottom of this hierarchical order, most lower-class Japanese tried to become colonizers until the end by maintaining the national identity of so-called 'Japanese-ness' and disciplining themselves to stay within that boundary. Only in this way could they take advantage of whatever they could from the colony as colonizers. However, some Japanese lived as colonists with Koreans, not as colonizers who ruled and enjoyed by ‘establishing a relationship’ with the Koreans who were colonized. A typical example of these people is Sueji Isogaya, imprisoned in the 1930s for engaging in a labor movement with Koreans at the Japan Nitrogenous Fertilizer Company in Heungnam, Hamgyeongnam-do. Of course, there are only a very few of these people, but their existence is meaningful in overcoming the past between Korea and Japan, decolonization, and the value of otherness.

The user can freely use the public work without fee, but it is not permitted to use for commercial purpose, or to change or modify the contents of public work.