동북아역사재단 2022년 04월호 뉴스레터

- Kim In-hee, Director, Korea-China Relations History Research Institute

Jingji Tun, a Small Island in China

Jingji Tun (Gyeonggi Village) is a Korean village located in Wuxing, Zhangjiadian, Liuhe, Tonghua, Jilin, China. I first learned about this village in the mid to late 1990s when I was studying in Beijing. I visited the house of someone I was close to, and the lady that took care of the housework spoke Korean very well.

“Ma'am. How can you speak the Seoul dialect so well?”

“Everyone in this village is like me.”

"Really? Where did you learn it?”

“Everyone here came from Gyeonggi-do. My parents came from Yongin, and my in-laws came from Anseong.”

After studying in China, I returned to Korea to work as a lecturer at a university. I went to Anseong about once a week to give lectures. After the lecture, I visited the Anseong-gun Office to see if there were any records of people who emigrated during the Japanese Occupation. Surprisingly, there were such records, including the exact dates. I took students to Jingji Tun, twice in 2000 and 2001 to investigate the migration history and life of the people there.

As of 2000, 296 people were living in 76 households. Because all the villagers originally came from Gyeonggi-do, they named the village Jingji Tun (Gyeonggidun). After it was known that the people of Jingji Tun speak standard Korean, it was reported that the newscasters of Yanbian Broadcasting Station often visited this village to learn Korean. In addition, they said that the students from Zhongyang National University in Beijing and Yantai University in Shandong came here to practice Korean.

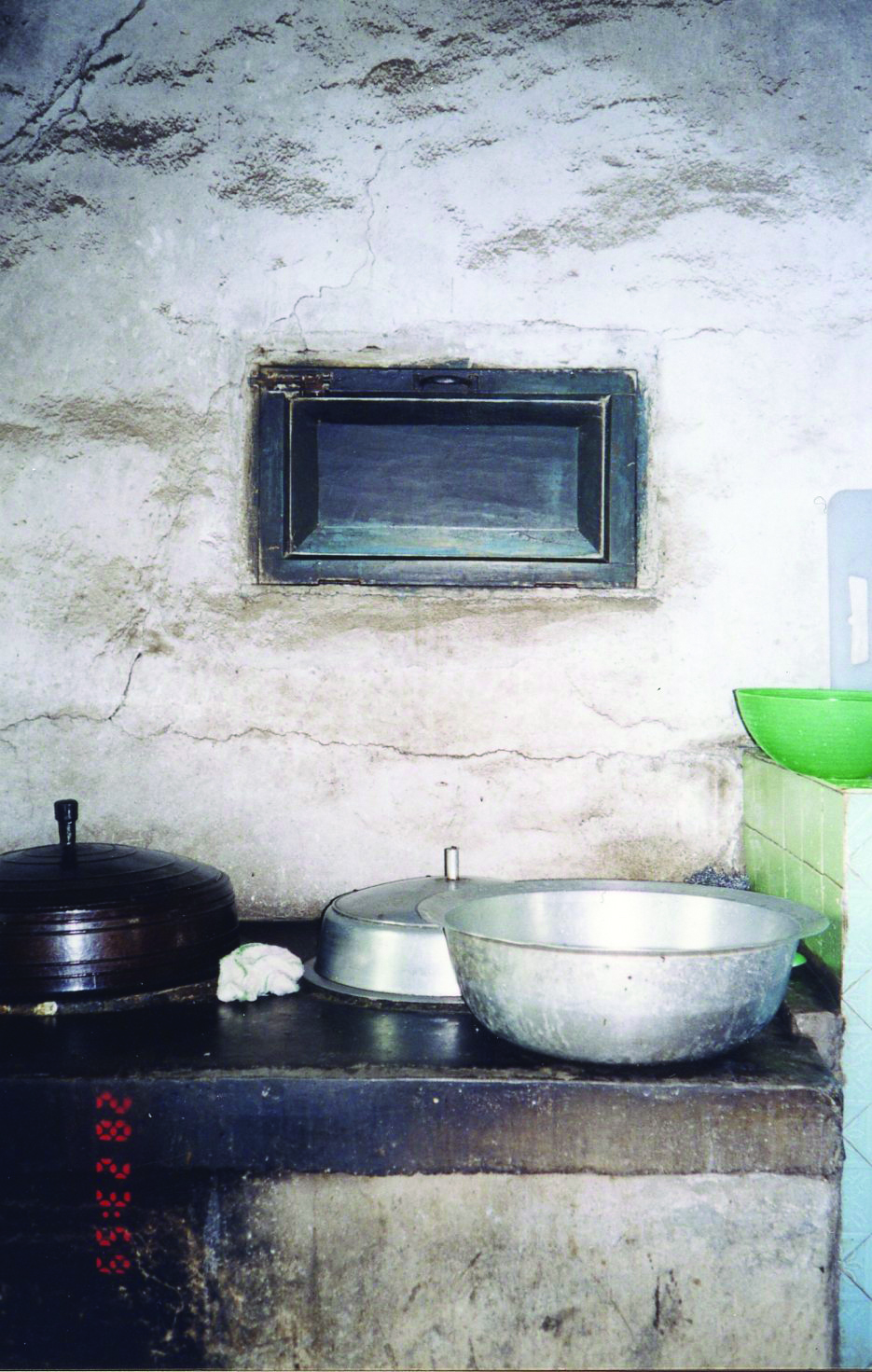

Although it has been 60 years since people moved to Jingji Tun, they have maintained the way of living just as it was in Gyeonggi-do, South Korea, in terms of language, food, house, and lifestyle. They have soybean paste stew, use ashes to take care of excrement from traditional toilets in a thatched house, and they wear hanbok (Korean costume), play janggu (Korean double-headed drums), and sing Arirang (Korean song) on important days. Jingji Tun is basically a small island in China.

Immigration through Employment by Japan

The Jingji Tun people were residents of Gyeonggi-do, emigrated by Japanese imperialists to secure military provisions when the Pacific War was coming to an end in the 1940s. The Japanese advertised, “If you go to Manchuria, you will have enough food and live well,” and “We will give you land and a house.” On March 16, 1940, 50 families arrived at Jingji Tun, and the Japanese greeted them with Japanese flags.

The Japanese imperialists took the houses of the Han Chinese by force and gave them to the Jingji Tun people. For this, the Han Chinese became antipathetic to the people of Jingji Tun. The Japanese imperialists deliberately implemented this policy to promote conflict between Koreans and Han Chinese. Local Han Chinese swore at Koreans as 'Gaoli bangzi (Korean Bats),' which means "Koreans fighting with bats." Koreans had animosity toward the Han Chinese in that when they broke bricks, they said, “Break the heads of Chinese.” There are also funny anecdotes. Koreans told the Han Chinese that 'old Korean gentleman' was an insult to Korean deliberately, and the Han Chinese used to call Koreans 'old Korean gentleman,' thinking that they were cursing Koreans.

The Manchurian Development Company established collective villages to monitor the Koreans and prevent them from building ties with independence activists. A 4-5 meter tall earthen wall was built around the village to prevent attacks by Han Chinese and bandits. At the time, many people died from unknown diseases. The village was moved to the current location in 1949, thinking that the water from the well was the cause. People that suffered from the disease lost their hair. At that time, in one family, both parents died, and only a boy survived. They wrote the Korean address on his back and sent him to Korea on a train. After the exchange with Korea began, they said that the child returned to the village as an adult.

In Jingji Tun, winter came early, and there was little precipitation. They could not manage to meet the time for sowing, weeding, and harvesting. Rice seeds they brought from Korea did not grow well in this new land. After two or three years, the rice seeds the Japanese imperialists distributed also barely adapted to the local environment. Japanese imperialists plundered most agricultural yields under the pretext of taking the cost of emigration, land, agricultural equipment, and cattle rental fees. Villagers would dig the ground under the toilet to hide rice to avoid exploitation by the Japanese imperialists. They were told they could return to Korea once they repaid the debt they owed when they moved to the Manchurian Development Company, but they could not afford it due to poor yields and plundering.

The hunger they felt at that time was indescribable. The Japanese imperialists plundered crops and distributed rotten millet and millet for fodder, but it was not enough to appease hunger. They ate everything that they could eat to survive. They ground fatsia roots or millet husks to make a paste and had them like rice cakes. They even peeled tree bark and ate it. At that time, many people died from swelling because they could not eat.

Of the 50 households that migrated, seven to eight families returned to Korea, and six to seven families died. At the time of national liberation, only 27 families remained. The 60 years that the residents of Jinji Tun have experienced show the typical life of the Korean people who immigrated as farmers toward the end of the Japanese Occupation.

Make the Gate Facing East

When

the people first arrived at Jingji Tun, they built houses in Gyeonggi style and

made the gate facing east. It was an effort so as not to forget their hometown in

the east, where they came from. Even the cold wind of Manchuria could not stop

their longing. In the movie

Correspondence with Korea began in 1983. Exchanges had already taken place via Hong Kong in 1989, before the establishment of diplomatic ties between Korea and China, and in 1990, three people visited Korea to see their relatives. After establishing diplomatic relations, many people interacted closely with Korea to visit relatives. Lee Gyeong-ha studied forestry at a university in Harbin and studied in the Soviet Union. He used to live in Anseong and moved here when he was fifteen. He said he wanted to go back to his hometown, but he couldn't because he was sick. He says that he vividly remembers picking up chestnuts in Anseong and eventually shed tears.

Although it has been more than 60 years since the people moved to Jinji Tun, they have maintained the customs of Gyeonggi-do in terms of language, food, house, and lifestyle. They also married people inside the village, so they have a saying, “We have in-laws every other house.” When they first arrived at the village, they set up a night school to teach Korean not to forget the Korean language. According to the elderly, “My fingers were pencils, and the yard was the notebook.” Such efforts helped the people of Jinji Tun not forget Gyeonggi-do's language.

They said they often listened to Korean radio broadcasts and felt happy to listen to Korean songs, although they don't understand them well. They listen to the program called ‘Along the Time, Along with the Song’ a lot. They enjoy the Lunar New Year and Chuseok holidays, swinging, wrestling, and jumping on seesaws. The cauldrons, wooden rice chest, wardrobe, spoons, and brass bowls they brought from Korea still maintain their lives.

동북아역사재단이 창작한 '중국 경기툰 사람들의 고향 생각' 저작물은 "공공누리" 출처표시-상업적이용금지-변경금지 조건에 따라 이용 할 수 있습니다.