동북아역사재단 2011년 10월호 뉴스레터

- Lee Kidong, Chair Professor at Dongkuk University

East Asia in the 8th century enjoyed unusual peace and prosperity within the regional structure formed with Tang in the center. The period saw Silla, Balhae and Japan making unprecedentedly frequent communications with Tang, and although Silla and Balhae were hostile towards each other, both maintained close relations with Japan. Within this regional order, remarkable progress was made in the areas of cultural exchanges and trades between countries in the region.

Some Japanese historians in the past used to argue that the concept of "East Asian World" could be theoretically systemized on the grounds that the international relations among the three countries were formed by means of the Chinese emperor bestowing titles and honors on the rulers of Korea and Japan and that under this regional structure of international relations, Korea and Japan actively adopted the Chinese legal system and culture. However, this theory of "East Asian World" was counter-argued by others. The counter-arguers drew attention to the differences that the East Asian countries displayed despite their superficial similarities in political forms, class systems, land distribution systems and governing manners of the peasantry in the 8th to 9th centuries. The East Asian countries tended to have fundamentally different social bases. There were structural differences among the countries due to their different stages of historical development.

Silla and Balhae, Playing a Role of Mediator between Japan and Tang

The counterargument certainly has some plausible points. The theory of 'East Asian World' lacked critical insight to overcome the limitation of one-state history because it was centered on the uniqueness of Japanese history. Looking at the historical trend of East Asia around the 8th century, moreover, the relationship between Korea and Japan was as much as or sometimes even more important than their respective relationship with Tang. For example, during the 30 or so years from about 670 to the early 8th century when both Silla and Japan stopped any official relations with Tang, the two countries maintained close relations with each other. During this period, Japanese scholars and monks who accompanied diplomatic envoys to Silla and studied there brought to their country Silla's scholarship and philosophy including its political system based on codes of laws and ethics [律令 政治制度] (although it was a system Silla had adopted from Tang and modified). In particular, the influence of Sillan Buddhism is considered to have been absolute while Japanese Buddhism, which still remained as "Clan Buddhism" during the Asuka [飛鳥] period, developed into "State Buddhism" in the Hakuhou [白鳳] period.

This type of interactions was not limited just to the relationship between Silla and Japan. Throughout the 8th century, Japan sent envoys and students to Tang via Balhae or received recent news about Tang from Balhae. Sometimes, they even made contact with their envoys and students in Tang through Balhae envoys. It was through their envoys to Balhae that the Japanese court learned the news of the An-Shi Rebellion, albeit a bit late, and they relied much on the help from Balhae for their envoy to Tang, Fujiwara Kiyokawa's [藤原淸河] safe return when he was over-staying in Tang after having failed to make a voyage home. Balhae played a series of more mediating roles between Japan and Tang, from dedicating a Japanese dancing woman to Tang as a tribute, to procuring Buddhist scriptures, and to importing Tang's rare, luxury items such as a goblet made of hawksbill sea turtle and musk; there seems to have been no area that Balhae's mediation did not take part in.

Looking at the Center from the Peripheries of 8th Century East Asia

(Picture 1) The Shosoin Treasure House

(Picture 1) The Shosoin Treasure Houseof Todaiji Temple in Japan that shows

the diplomatic history of 8th century

East Asia at a glance

Most existing studies on cultural exchanges in East Asia focus their sight on the center and look out to peripheries as they assume that the central culture spreads to peripheries. However, the phenomenon called "peripheral creativity" presents us the necessity to look at the center from peripheries. During the 7th to the 9th centuries, East Asia established their own sphere of Buddhist culture, in which the Buddhist culture of each country in the region was connected to each other transnationally and organically, forming one network of Buddhist culture. The East Asian sphere of Buddhist culture was, of course, shaped with Tang in the center, but it does not mean that contributions of peripheral countries to this sphere of culture are negligible. For example, the Buddhist scripture Vajrasamaadhi-sutra [金剛三昧經] is apparently a pseudoepigrapha, since it was not included in Daejuganjeongrok [大周刊定錄] (695), an annotated collection of authentic Buddhist scriptures published during the Tang period. However, since the Silla Monk Wonhyo (617~686) had written The Exposition of the Vajrasamadhi-sutra [金剛三昧經論], the Vajrasamaadhi-sutra should have been already introduced in Silla. Some researchers of Korea and the United States speculate that the Vajrasamaadhi-sutra, a Buddhist scripture with an uncertain origin, might have been written by a Sillan Monk. Judging from this gap of scriptural information between the two countries, we can also speculate that although Silla and other peripheral countries including Balhae and Japan paid tribute to Tang to show respect and fealty, the Buddhist circle of those countries subtly resisted Tang's authority.

The History of 8th Century East Asia is composed of 12 articles that investigate the historical aspects of the 8th century in which East Asia had historically the most stable regional structure and state, looking from periphery to center. These articles cover various topics, which are classified and arranged into three parts: Part I – three articles on the overall international relations in East Asia; Part II – six articles that deal with each of the East Asian countries; Part III – three articles on special topics.

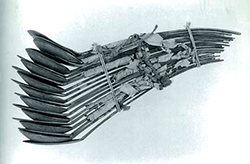

(Picture 2) A Sillan spoon exported to

(Picture 2) A Sillan spoon exported toJapan, which is preserved in its original

wrapper in the Shosoin Treasure House

Part I provides an overall description of 8th century East Asia mainly based on the research findings accumulated so far. The historical stance of the academic circle of each country, Korea, China, and Japan, is well revealed in the articles. Wang Xiaopu [王小甫] (Professor of Beijing University), for example, argues that the "strategic partnership" between Tang and Silla balanced and stabilized the region, but he does not agree that the Unified Silla and Balhae together are part of Korean history as a North-South period. Meanwhile, his macroscopic insight shows in his observation that 8th century East Asia was being transformed from a local society to a pluralist society.

The articles in Part II describe foreign relations of four countries, Tang, Silla, Balhae and Japan. Yeon Minsoo (Research fellow of the NAHF), who discusses the Silla policy of the Japanese royal court, gives a detailed account of the diplomatic friction between Silla and Japan involving etiquettes towards foreign envoys [賓禮]. According to Yeon, Silla's unification of the three states in the Korean peninsula became the source of Japan's hostility towards it, and Japan legislated the etiquettes as it was establishing itself as a Tenno-centered Ritsuryo state (i.e. a state ruled by an emperor in accordance with legal codes) that surpassed Silla's state system. Since then Japan imposed on Silla to observe the foreign envoy etiquettes, but Silla, regarding them as a nuisance, refused more often than not, causing diplomatic conflicts that ended up in a disaster.

Part III has articles that deal with special topics such as Tang, Silla, and Japan's capital city systems, Buddhism exchanges, and maritime trades. Sakaue Yasutoshi [坂上康俊] (Professor of Kyushu University), in particular, discusses similarities and differences between Silla's Bangrije [坊里制] and Japan's Jobosei [條坊制], both of which were copied after the Chinese Duchengzhi [都城制]. His paper presents new directions for future research on East Asia's capital city systems.